Sacred or profane? Thoughts on objects in ethnological museums

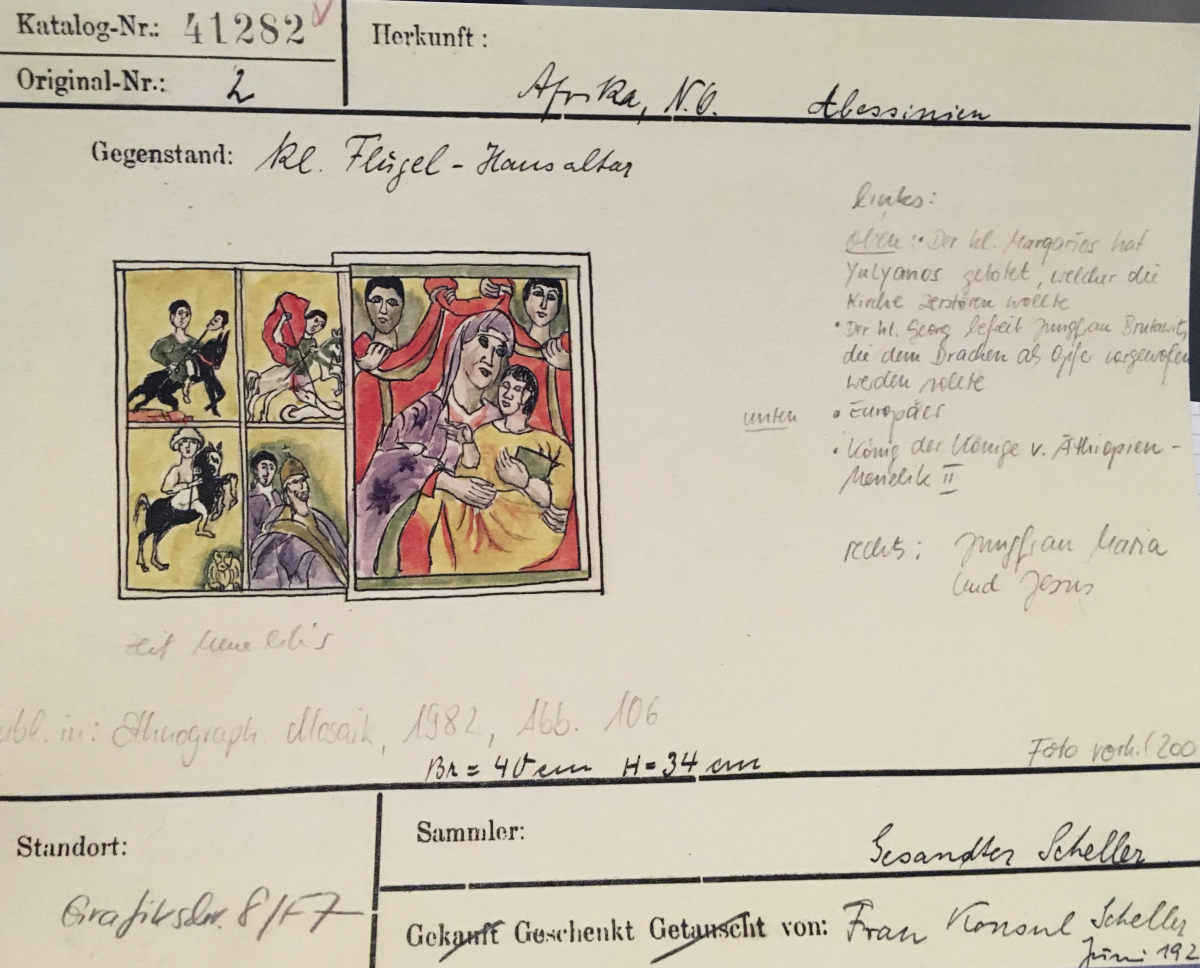

Catalog card of the small winged house altar by Fre Heywat. Photo: Foteine König.

Catalog card of the small winged house altar by Fre Heywat. Photo: Foteine König.By Foteine König (KFG "Multiple Secularities")

With the exhibition Prolog Werkstatt, the Leipzig Museum of Ethnology is currently exploring the colonial past of its collection. A central aspect here is the question of how ascriptions to objects in the museum differ from their original contexts, which perspectives are reflected in them, and which interpretations are thus also given to visitors.

"And now I do not know who I am anymore. Sacred? Profane?" This question comes in a whisper from a wooden box. The voice trembles, seems insecure and no longer certain of its own identity. It is the voice of a small winged house altar made by the Ethiopian artist Fre Heywat between 1909 and 1910. Like many other collectibles, the altar can currently NOT be seen in the Prolog Werkstatt exhibition at the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig. Not to be seen because this part of the exhibition – Whispering Boxes – hides its objects in boxes and lets them tell the visitor about their history through an audio installation. Besides the classic icon depiction of Mary and the Infant Jesus, this altarpiece also portrays the German consul in the Ethiopian Empire Robert Scheller-Steinwartz (whose wife donated the altar in 1926 to the museum) and the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II. This combination, peculiar for altars and at the same time typical for this kind of colonial “souvenir”, causes the identitary insecurity of Heywat’s altar: sacred or profane?

Whilst this distinction here refers more to the souvenir character of the altar, it also plays a fundamental role regarding museum presentations in general. Thus, an accompanying text of the exhibition ends asking: "How does a museum change the status of things and how do museum actors determine the way an object is perceived?”

If objects are defined or named in relation to their original meaning, i.e. the reason for their manufacture, René Magritte's famous inscription “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” under the image of a pipe, can be further explored in the context of objects exhibited in a museum. Is a fork still a fork if it is not used to feed food or is it rather an object that resembles a fork on the outside or maybe an object that used to be a fork? Accordingly, objects are essentialized, but this attribution of essence is never static, but rather changeable in the context of the environment and human interaction with the object.

This is particularly interesting in relation to sacred objects. The statue of a deity serves here as an example. First there is the (supposedly) authentic meaning of the object, the reason for its manufacture – for example the worship of the statue during sacred ceremonies. In the next step we look at the object in the museum, a place that legitimizes itself through the symbolic and representational power of things and largely pursues a pedagogical and secular claim. Objects previously used for religious purposes are snatched from their sanctity in this context, but also take on the role of a container of religious history (Bräunlein 2017: 38) as a mediating medium.

At this point possible hierarchies of meaning attribution can come into consideration. While everyday objects such as the aforementioned fork, which normally disappears in a kitchen cupboard with several forks of its kind and has no particular significance, is ennobled by the presentation in the museum into a mysterious and dignified sphere, which Peter Bräunlein describes as auratic (Bräunlein 2017: 31). But how does this apply to objects that already have an exceptional – not profane – symbolic power in their origin? To speak of nobility because they are inside a museum seems strange when it comes to religious objects. Although they are attributed character traits of works of art, at the same time a secular quality seems to unfold maybe even changes them altogether, since the museum always prevents the religious practice in which the object was previously placed. The statue of the deity is no longer visited by people who want to come close to a transcendental power through it, but by more or less curious museum visitors who are not always enthusiastic about the true meaning of the object, but perhaps only admire its historic or aesthetic aspects. The visitor’s perception can of course be guided by the museum presentation and contextualization, but neither can it be determined nor experienced in a way that could give it credit.

In addition to the fact that the exhibition Prolog Werkstatt questions the concept of the ethnological museum itself and serves as preliminary work for a new permanent exhibition, the Grassi Museum asks visitors to contribute to these preparations and to rethink their ideas about the allegedly unknown other as well as their own daily life. The workshop-like exhibition emphasizes the political side of museum work, especially concerning traditional ethnological collections, but goes beyond them when dealing with current social debates about identity, racism, and global inequality. This is most clearly shown by a film documentation about the return of human bones from the Free State of Saxony to a Hawai’ian delegation in October 2017. Human bones that have long been exoticized and objectified as colonial treasures in Northern/Western museums are supposed to be rehumanized through the act of return. Rehumanization is a challenging word, as if they had ever been anything other than human. Questions of what (or who!) is exhibited in a museum and who visits with what perspective becomes a whole new meaning and relevance if we look at cases like these and the history of ethnological museums in general. One cannot or does not want to imagine what the human bones would have asked if they had been in the whispering boxes.

References: Bräunlein, Peter J.: “Die materielle Seite des Religiösen. Perspektiven der Religionswissenschaft und Ethnologie.” In Architekturen und Artefakte. Zur Materialität des Religiösen. Edited by Uta Karstein, Thomas Schmidt-Lux, 25-48. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2017.

Screenshot from prolog-ausstellung.info

Screenshot from prolog-ausstellung.info